Join us on a trip inside the Bang & Olufsen “torture chamber”, where a man is tasked with destroying our products, all in order to obtain the highest possible quality level.

Testing to the limit

Join us on a trip inside the Bang & Olufsen “torture chamber”, where a man is tasked with destroying our products,

all in order to obtain the highest possible quality level.

Electric blue flashes from a stroboscope light up a printed circuit board strapped to a giant speaker. The frequency is turned up and the speaker howls like a slide whistle. It settles on a single intensifying note - when the frequency reaches the print board’s resonance – and the multicoloured electrical wires weave in slow motion as if they were being snake-charmed.

In the background, you can hear the chugging and clanking sounds of a boxed-up TV being put through its paces on the “prairie wagon”, a machine that mimics the shakes and bumps you would find on a particularly dodgy stretch of the Autobahn. This sensory kaleidoscope of sounds and lights - part 60s sci–fi soundtrack, part industrial techno - reminds me of that spirited moment in Lars Von Trier’s Dancer in The Dark when Björk turns factory whacks, bangs and crashes into beats and music.

We are in Bang & Olufsen’s reliability lab in Struer, a series of basement workshops affectionately known by those who work here as the “torture chamber”. This is where all products and components – from circuit boards to remote controls and headphones – are put through rigorous and painstaking tests to guarantee reliability, quality and durability. A place where immaculate design objects are treated to beatings, scratches, chain-smoking and violent temperature swings to make sure they are future-proof.

Holding the stroboscope is Peter Loff, a reliability test engineer who has been with Bang & Olufsen since 1996. Dressed in jeans and blue–and–red chequered shirt, he’s hardly the goggle-wearing mad scientist, but his remit is essentially to search and destroy. On the strobe–lit electric circuit boards, he is looking for components that show sign of instability and will need extra solidification in forms of glue or

screws. It is product testing before the final product has even taken shape. “We have a close relationship with designers and engineers to make sure we can start these tests before the final version is created,” says Peter. “The earlier we can spot a weakness, the better.”

He guides me through myriad machines, ovens, chambers and work stations. Hand cream, discount ammoniac cleaning product and a bottle dispenser with sweat (made from salt and acetic acid) are laid out on a table to test surfaces on a speaker; small lead weights covered in sand are used to scratch plastic and aluminium covers. There is a “tropical chamber” with 93% humidity where products can stay for 42 days to test for corrosion, while xenon lamps put speaker cabinets under the spotlight for four days to create the effect of intense sunlight.

BeoVision Avant gets a heavy dosage of cigarette smoke.

An old 64k microcomputer used to control simulations.

Perfecting products by pursuing breaking point

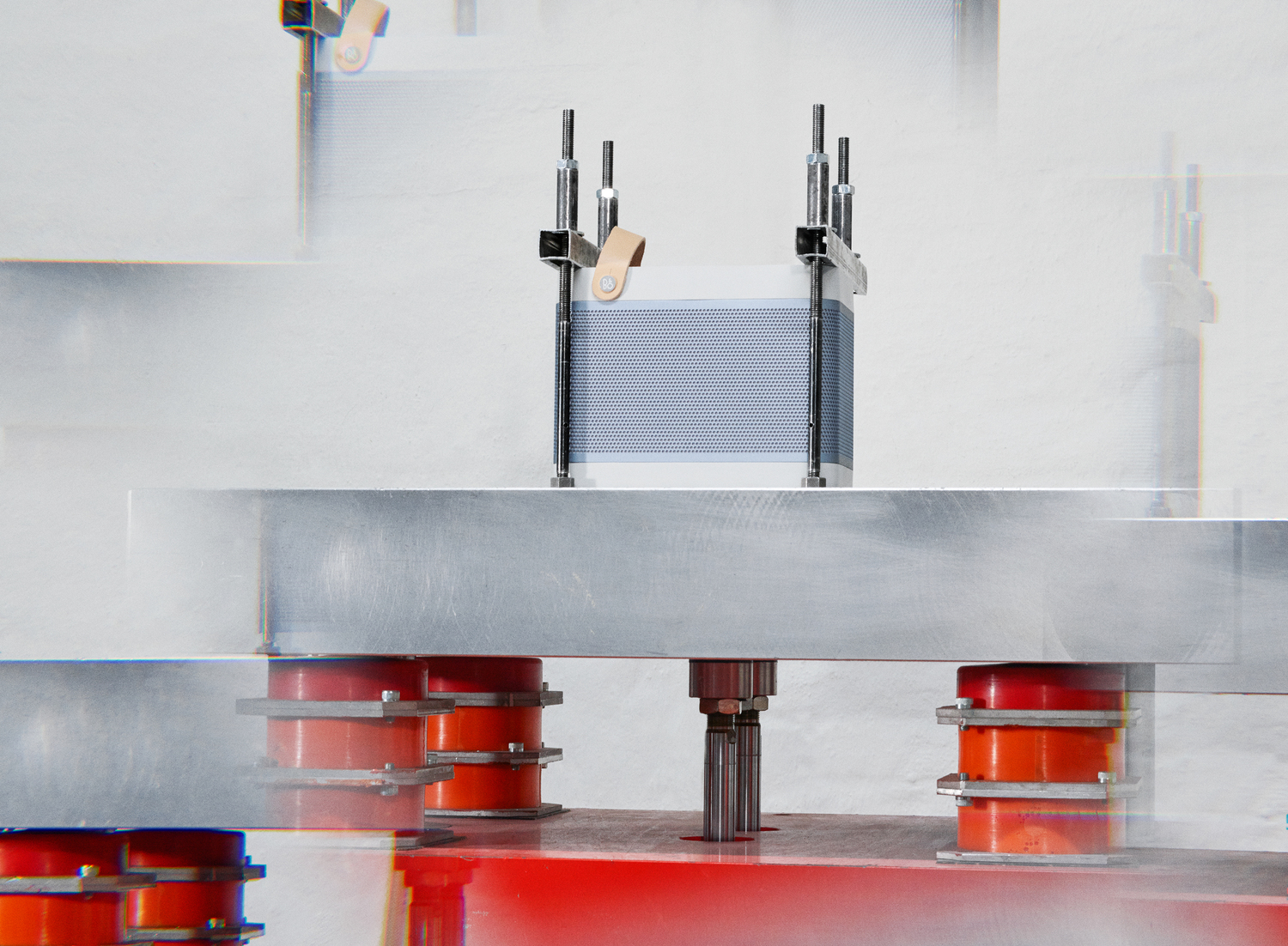

The most strenuous test of all is HALT - the “highly accelerated life test”. The acronym sounds like a descendent of Kubrick’s sentient computer from 2001:

A Space Odyssey, and there is also a somewhat menacing aspect to its purpose. The HALT test is carried out in the Qualmark Typhoon 3.0 chamber, a system favoured by carmakers and the military, where products are shaken, exposed to extreme temperatures and taken to the brink of breaking point.

Jens Hjorth Drejer, an audio engineer, drills holes through a prototype speaker before attaching probes and wires so they can control the inside temperature during testing. The small speaker is blaring out the track A Warrior’s Call by Danish

hard-rockers Volbeat, but it looks decidedly disarming as it sits in the Typhoon chamber behind seven layers of tempered glass. Doors are sealed before elephant–trunk-like tubes pump nitrogen into the chamber. The sound is encapsulated inside, but the signal is measured on a computer monitor as they lower the temperature. With a range stretching from minus 100 to plus 200 Celsius, and the ability to switch 70 degrees within a minute, HALT represents the most cutting–edge technology - and the perfect tool for chilling schnapps and beer at the Christmas party, as long as you don’t start the vibration cycle.

“We need to go beyond the specs with our products,” says Turi Bach Roslund, a reliability engineer working on the HALT test. “If we only work within the specs then we don’t have any design margin and then there is a risk that a pair of headphones or a speaker can get worn down.”

So what does it feel like to drill through, break down and beat up the craftsmanship and meticulous design that their colleagues have worked months and years creating?

“We have engineers who sit next to us during the testing when we spot an error,” says Turi. “My colleague and I will be punching the air - yes! - but they look gutted because we have just destroyed their baby. We are thrilled when we can spot a mistake - because then it never reaches the customer. We know how much trouble we can save them and how much money we can save. However, I must admit, the first time we had to take a product apart, it hurt a bit.”

Peter is standing next to her smiling: “But you get over that.”

Beolit 15 getting roughed up by the "prairie wagon"

Chain-smoking machines

and floppy disks

The exposure to nature’s elements - sun, frost, heat - is posing new challenges for the B&O PLAY series and its portable audio products. While Bang & Olufsen has decades of experience in testing TVs used in a traditional home setting, the application of headphones and Bluetooth speakers is much more individual and inventive. “We might have ideas about where you would place them, but people will take their speakers to the beach or use their headphones riding mountain bikes,” says Peter. “It is important that we learn about these behaviours so we can design the right tests. If we are developing new speakers, we want to know how they are being used. If they are being used near a swimming pool, then we have to factor in high humidity, heat, sunshine and chlorine fumes. We have to make sure that all materials and components can handle the elements.”

Much of the test equipment is from the high-tech range, but there is a beautiful bit of digital nostalgia in the shape of a floppy-disk-fed computer from the early 1980s, which was originally developed for the BBC. In the Bang & Olufsen torture chamber, the old 64K microcomputer controls air cylinders that simulate the movement of fingers pressing buttons, including those on the top panel of the Beolit 15 speaker. It’s a movement, which is repeated in a seemingly endless cycle. “If a button on the speaker is going to be pressed one million times, then we just have to test whether it can handle this - and, of course, we are not going to sit here and do that ourselves.” No stone is left unturned in the meticulous reliability process, no esoteric avenue of inquiry is left unexplored. And no cigarette is left unsmoked. A Perspex glass chamber, covered with appropriately coloured yellow

film, is fitted with a dispenser that automatically lights non–filtered cigarettes and ejects the smoke into the test space. It smokes 120 cigarettes a day, a process sometimes repeated for 10 days, to check for discolouring and performance.

Peter opens a black box containing headphones - split apart, scratched, hacked, battered through various surface tests - and the cabinet from a Beolit speaker which smells like it’s been sitting in a dive-bar for the last decade playing nothing but Tom Waits; the smoke had left a nicotine-tainted star pattern caused by foam pads protecting the speaker.