Find out how David Lewis built upon the Bang & Olufsen design legacy by returning to original ideas.

Design Matters: Icons

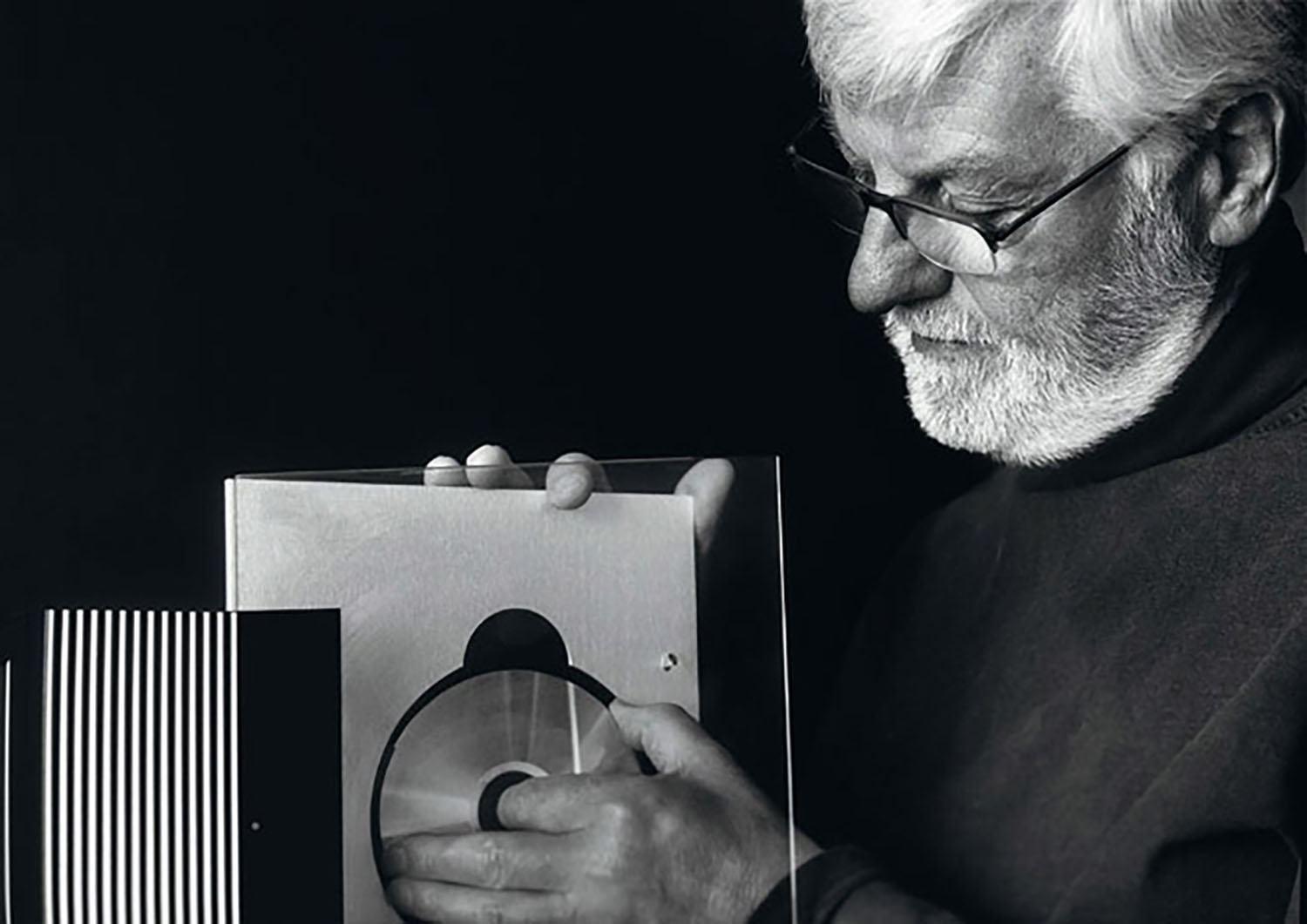

David Lewis

How did a Brit end up in Denmark leading the design on one of the country’s most esteemed companies? Read below to find out how David Lewis built upon the Bang & Olufsen legacy.

(Read about Jacob Jensen's design work for Bang & Olufsen here.)

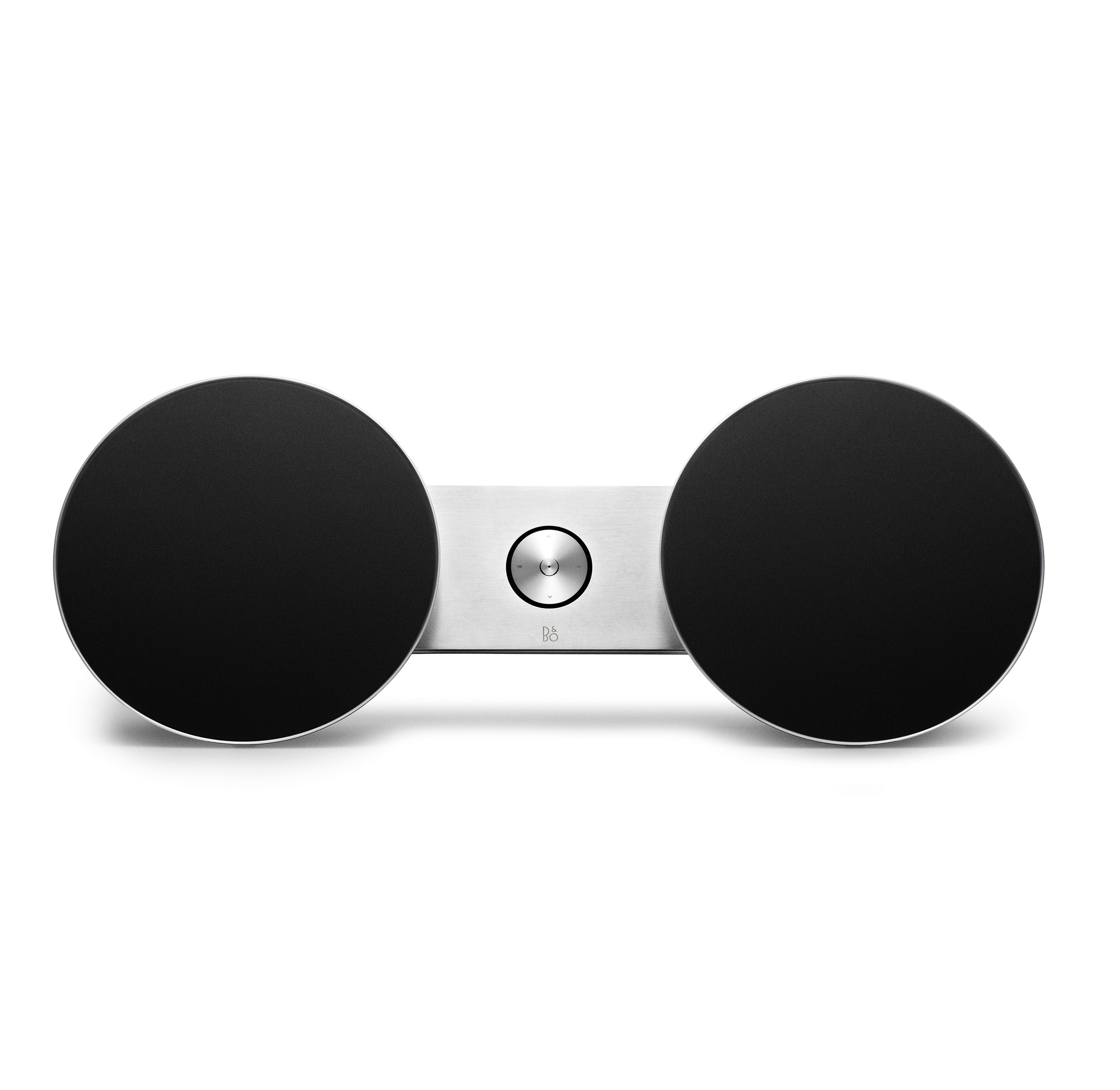

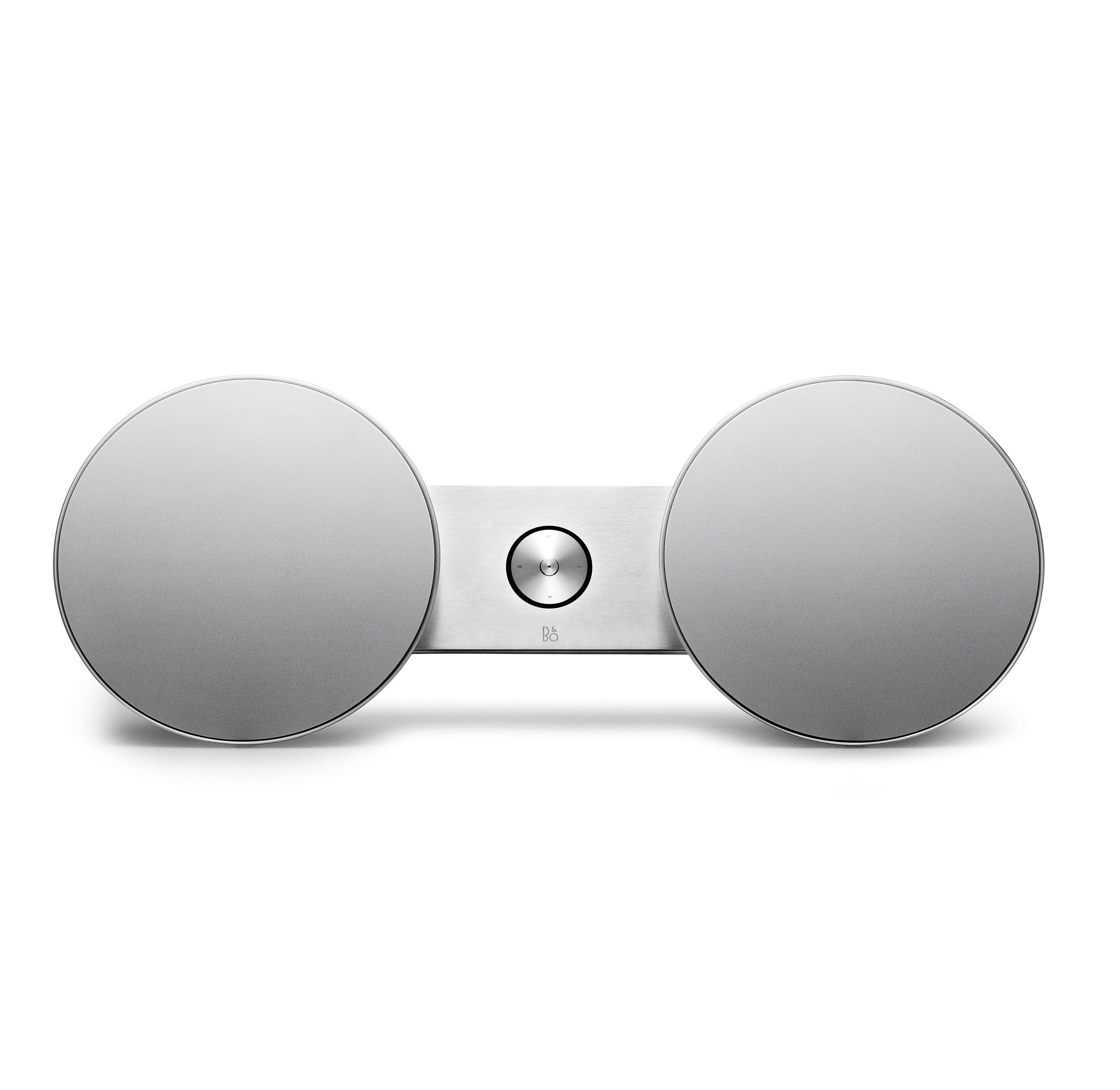

“Form is nothing more than an extension of content,” David Lewis told Beolink Magazine in 2003. “Who says that loudspeakers should hide away in corners, if the closer they get to you, the better they sound?” It's telling that Bang & Olufsen's chief designer's words almost exactly paraphrase those of the American writer and poet Charles Olson, writing in his manifesto, Projective Verse – music and poetry are, after all, both vibrating air, and Lewis was a master at creating devices to transmit the former.

From London to Denmark

Lewis was born in Britain in 1939 and graduated from London's Central School Of Art in 1960. Moving to Denmark a year later he began working for Bang & Olufsen under the legendary designers Jacob Jensen and Henning Moldenhawer. His first product was the Beovision 400 television set and early work included the Beolab 5000 system - he helped Jensen with its classic wood and aluminium design that won the iF Design award in 1967.

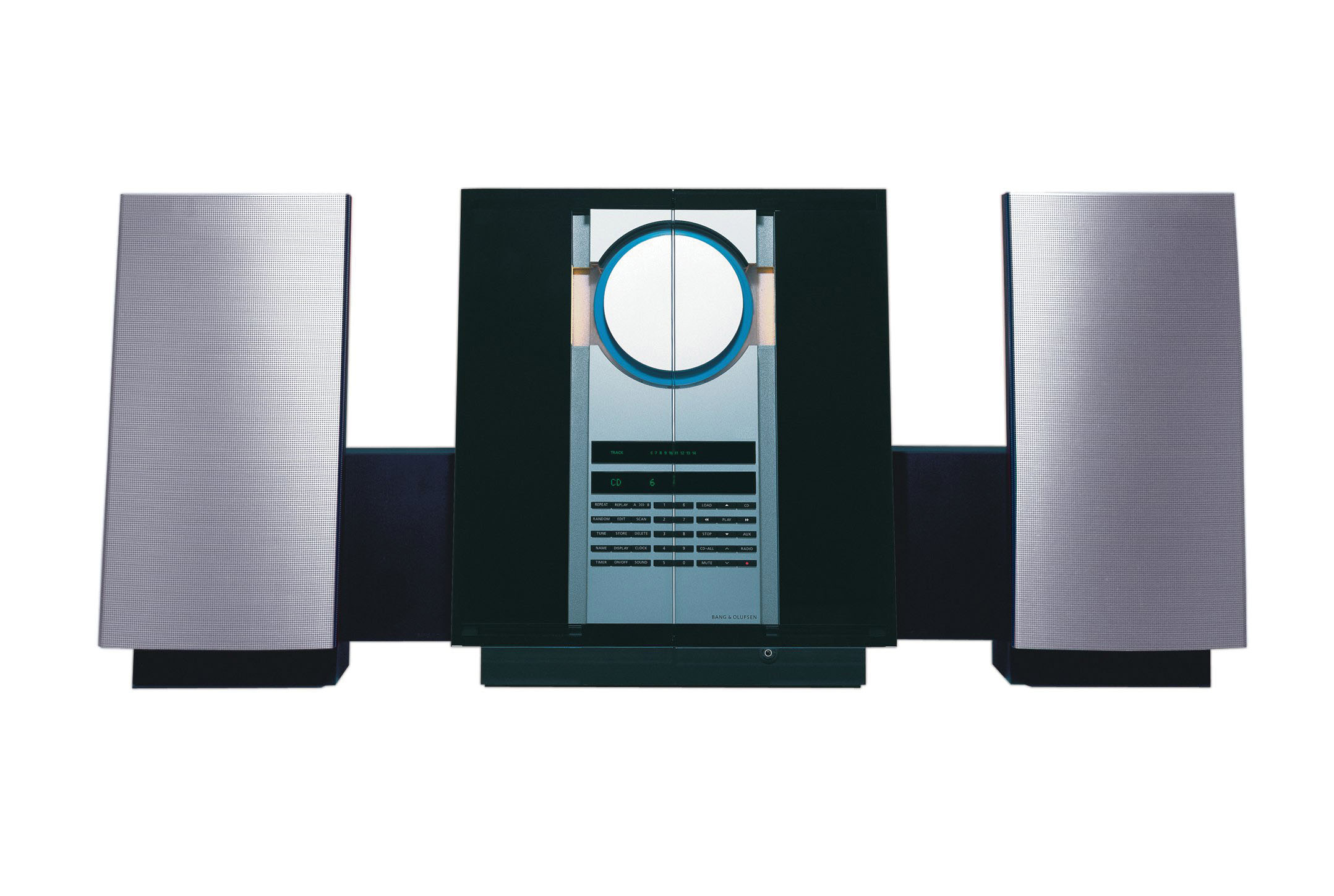

He founded his own practice, David Lewis Designers, in 1982 and throughout the rest of that decade their designs were the core of Band & Olufsen's output, especially as the company moved beyond stereo equipment and into the booming television market.

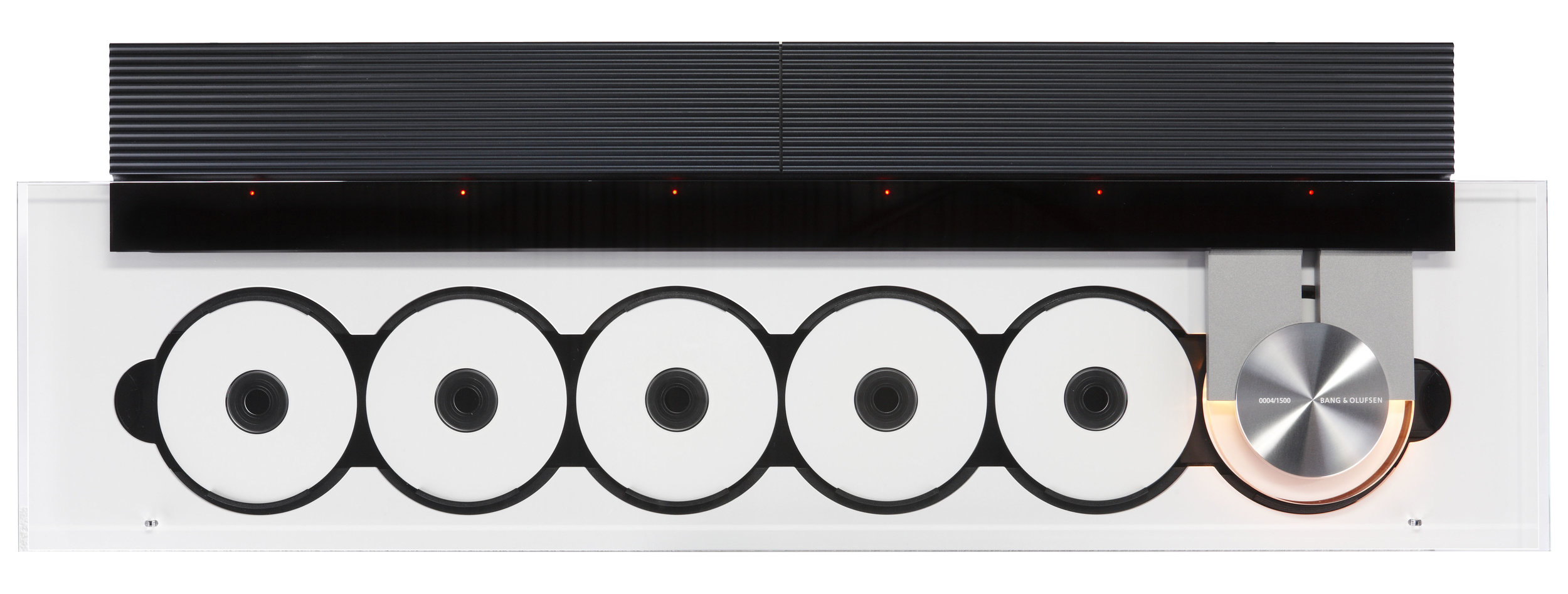

Innovations included the MX series, the first television sets designed by Bang & Olufsen. As ever, Lewis had a unique perspective. “As he sees it,” wrote Lewis’ right hand man at his studio in Copenhagen, Torsten Valeur, “when it's off, a TV is a cross between an aquarium and an eye peering into people's living rooms. Once the set is turned off, the design becomes paramount. Designing and creating a TV which also has a ‘life’ when turned off is the closest you can get today to giving consumers a good alternative to the empty aquarium.”

An evolution of elemental form

““We wouldn’t dream of doing something that wouldn’t hold. This is part of the culture.” ”