We visit London's Kew Gardens and meet the artist Wolfgang Buttress who guides us through his sculptural installation, The Hive.

Photograph by Jeff Eden

Enter The Hive

As he prepares for a performance, B&O PLAY visits London's Kew Gardens and meets the artist Wolfgang Buttress who tells us about his soon to be sonified sculptural installation, The Hive.

| CONTRIBUTORS |

| Words: LUKE TURNER |

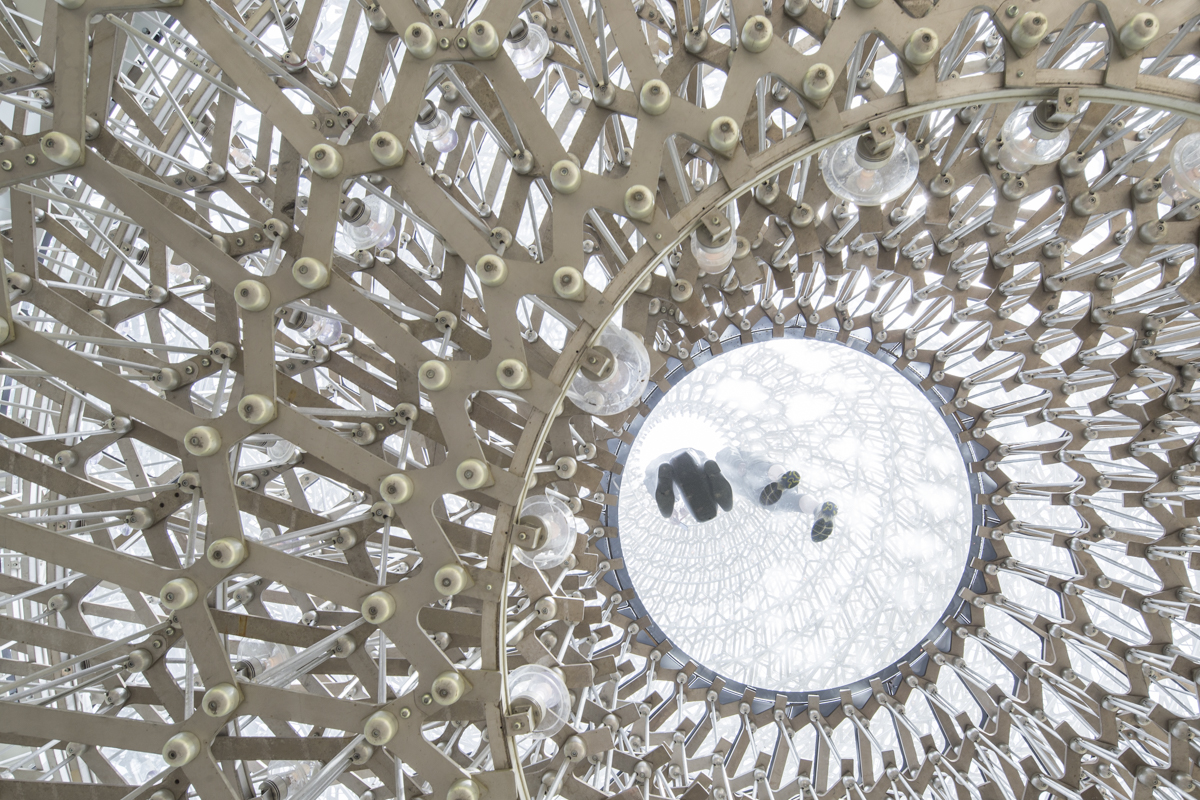

This week 60,000 bees and a dozen musicians will play a concert at Kew Gardens, the botanical park and arboretum under the noisy Heathrow flightpath in West London. The event, which might lay claim to being the gig with the largest number of living creatures in the history of musical performance, will happen at The Hive, a large sculptural installation by Nottingham-based artist Wolfgang Buttress. Originally housed at the 2015 Milan Expo, it appears from behind Kew's rare trees and Edwardian glasshouses as a strange cube with blurred edges hovering against a blue London summer sky. Approached by a ramp that rises along the top of a specially-planted wildflower meadow, the honeycomb-shaped aluminium struts gradually reveal a spherical interior, where people stand on a glass floor. A low hum becomes audible as lights inside the structure glow in varying intensities, and music starts to drift across the warm afternoon air.

From inside The Hive you're given a bees-eye view of flight across Kew's flower beds. "Usually as people in a landscape we're all-powerful human beings," Buttress says; "the idea is when you see people here they look a bit like bees or insects, it reduces us down. Maybe you feel more humble."

The architecture of The Hive certainly contributes to this sensation, blurring the human forms on the glass platform or beneath it. As Buttress explains, "I wanted it to feel like a swarm - you can't really understand the geometry until you get closer, and then it reveals itself and you see the structure is much like a honeycomb."

Just as in a beehive, every cell of the sculpture is different. There are 170,000 component parts, and each piece of aluminium was cut by high-pressure water jets that are more environmentally friendly than using heat. "The honeycomb in the hive is a perfect piece of architecture, a pure minimal form and so efficient," he explains. "Bees build it as big as the colony needs to be and they reduce it down, they regulate the temperature in it, they're really clean - there'll never be a dead bee inside the hive."

Photo by Mark Haddon

This cooperative spirit of the bees was reflected in the creation of the musical element of The Hive installation that makes the industrial-looking sculpture come to life. Buttress had always planned to have an audio element as part of the work, feeling it was the best way to make a connection between humans and invertebrates. "Just to have the sound of the bees would be great but this relationship with humans personalises it for the audience," Buttress says, "it focuses you in the space and makes you feel conscious of being with the bees, as part of nature."

Buttress invited musical friends, family members and members of Spiritualised and Icelandic folk group Amiina to a recording studio. Here, they listened to a live stream of a beehive, the cellist noticing that the sound of bees was in the key of C. Wolfgang's daughter, Camille started singing, improvising lyrics on the spot, and they began recording. "It was one of those moments, you had the sound of the bees, the singing and the cello, it was a proper epiphany," Buttress enthuses.

Between 40,000–60,000 bees live in the Kew Gardens hives, a few hundred metres from Buttress' sculpture behind a large glass and metal hothouse. Accelerometers in the hives measure the vibrations that indicate whether the bees are active, healthy and quiet, or if they're about to swarm. They can even pick up the bees 'conversations' as they communicate with the vibrations of the waggle dance. The signals are then passed through software which triggers some of the 150 musical stems that Buttress and friends recorded in the studio, creating a constantly-evolving, ambient musical wash broadcast through the speakers that cover the sculpture. There's a kinship both with Brian Eno's landmark ambient albums and his more recent interest in generative technology. Indeed, Buttress agrees there are parallels between the music for apiarists at The Hive and Eno's methodology of "embracing accident, chaos and happenstance".

The different musical parts were arranged into coherent pieces for release with a limited-edition monograph that accompanied the original installation. Shortly before The Hive came to Kew the music came to the attention of Jeff Barrett, founder of Heavenly Records and the Caught By The River website, who offered to release it as an album. The resulting long-player, called Be, started getting picked up by BBC radio and became a word of mouth minor hit, leading to live performances at festivals including an evening slot at Glastonbury. "There were loads of young kids raving, people bug-eyed," Buttress enthuses. At September's concerts, musicians will play on and around The Hive and an audience of 500, playing along with, and around, the 60,000 bees in Kew Gardens' hives. Each piece has its own structure but the bees will force the gig to take its own shape. "You have to give room for the bees to breathe," Buttress explains. "When you hit that sweet spot that's when it works. For us as artists and musicians that sense of letting go was really liberating."

Photo copyright Laurian Ghinitoiu

Photo courtesy Kew Gardens

Walking down the sloping earth ramp of the Hive, children stop and ask Buttress for photographs. "'Scuse me, are you the mister who made this?" asks one. Buttress seems unfazed by the attention, perhaps seeing himself as an extension of the bee ecosystem, using his work and collaborations to bring attention to one of the most important issues facing the natural world of which we all too easily forget we are a part. Only last month new research pointed to pesticides known as neonicotinoids as being responsible for a 10–30% reduction in some bee species. "There does seem to be a heightened consciousness of the problems facing the bees," Buttress says, discussing recent campaigns to ensure the pesticides remain illegal. "People feel so disempowered but this is something where you can make a difference, and actually make your life more pleasant - planting flowers, for example, is a simple, lovely thing to do".