Find out how back at the start of the 1900s, the first real innovators of synthesised musical instruments were Soviet Russians, working towards a musical revolution.

Sound Matters

Light Music

As part our ongoing series of articles, podcasts and videos celebrating sound in all its various forms, musician and writer Peter Kirn investigates the strange and wonderful history of Russian and Soviet visual music.

By Peter Kirn

Russia has put image to music in the form of Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, in Wassily Kandinsky’s vibrant abstract paintings and numerous oversized dramatic spectacles. But lesser known are the country's experiments with electrified visual music, particularly those conducted in the Soviet period. These strange, ahead-of-their-time inventions are now being reborn with a new generation of artists.

vision into reality

In theatre, dance and music, Russian and Soviet-era artwork used every available technology to achieve a trans-disciplinary, immersive aesthetic experience. They continued to innovate with machine-driven optics and light when many other electronic music experiments were left literally in darkness. And if the composer Richard Wagner only theorised about Gesamtkunstwerk, it was the Russians who attempted to turn their fanciful visions into reality.

In this age of electrified machines, Russia's fascination with visual music can be traced to its spiritual forefather, the composer Alexander Scriabin. He found esoteric, spiritual meaning in the connection between colour and sound, with different musical notes producing synesthesia – the merging of one sense with another. To recreate the stimuli in his mind, he even added a line for colour organ ("clavier à lumières") to his mystical tone poem Prometheus: The Poem Of Fire from 1910. That creation splashed colour around the theatre in time with shifts in the music.

city as symphony

In early Russian visual music creations, you find a connection between music and painting. Futurist Vladimir Baranov-Rossiné's "Optophonic Piano” instrument created in 1907 employed hand-painted discs, spun in front of lights by a mechanical apparatus controlled from a keyboard.

Avant-garde composer Arseny Avraamov (1886–1944) was known for ideas like his raucous Symphony Of Factory Sirens. This work used an entire city as its instrument – employing factory sirens, automobile horns, the foghorns of the Soviet naval fleet alongside machine guns, cannons airplanes, a large band and choir performing the socialist anthem “Internationale”, among many other elements – all to create a massive-scale composition.

Ornamental Sounds

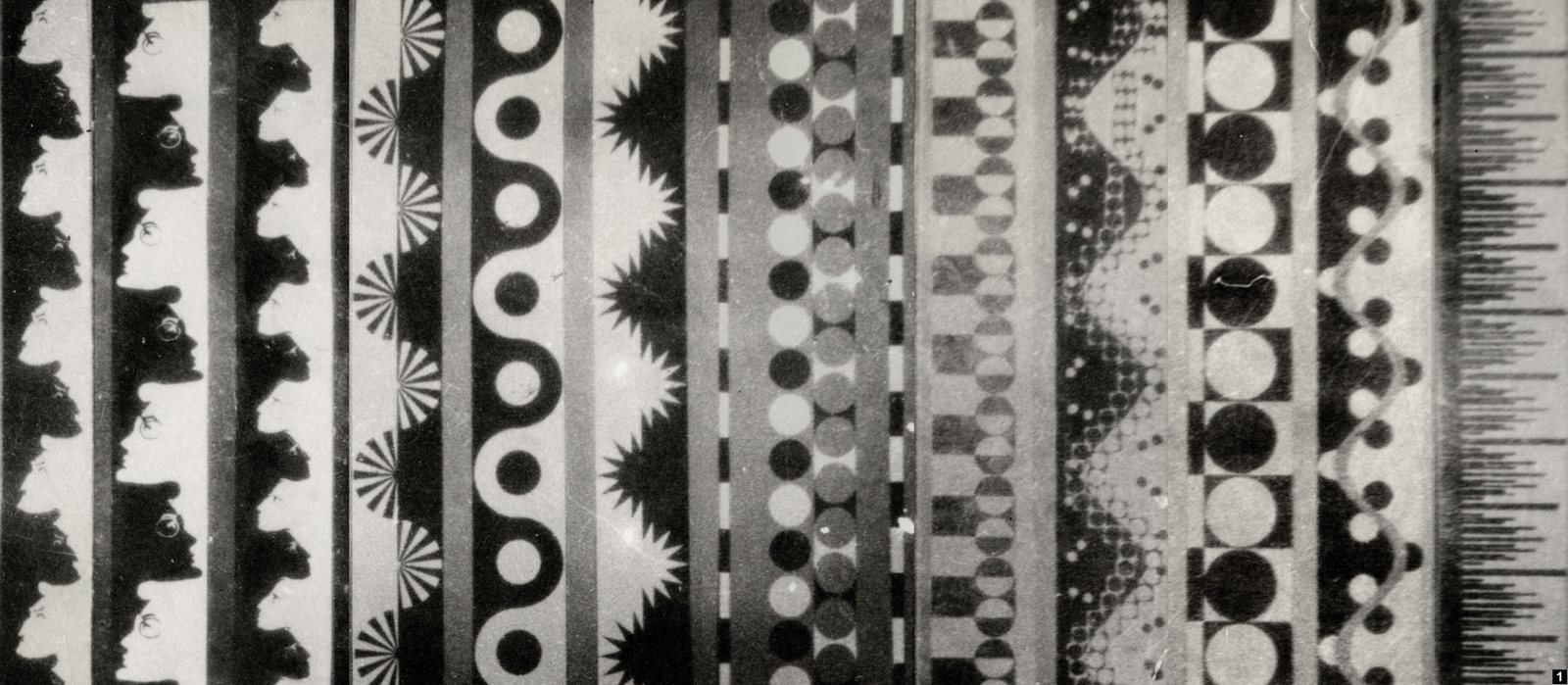

Avraamov also worked in visual music. Alongside Alexander Shorin, Evgeny Sholpo, and others, he developed a sonic technique that involved painting directly onto film, coinciding with the rise of optical soundtracks in the 1930s. Since that production method would render sound from light, the sonic patterns they produced anticipated synthesized sounds decades before the rise of the modern synthesizer.

Initially, these experiments were crude: hand-cut paper or detailed paintings of patterns producing simple tones and melodies one at a time. But – never ones to shy away from ambitious engineering – the Russian experimentalists developed entire machines around the photoelectronic concept. Sholpo's 1930s Variophone produced several tones at once, using hand-cut cardboard discs spun in sync with music, what he called “ornamental sound,” both visual image and sonic artefact. The device is credited with the first-ever artificial soundtrack for a now-lost 1930 film titled The Year 1905 In Bourgeois Satire then going on to be used in making soundtracks for Soviet animation, as well as collaboration with famed composer Georgy Rimsky‐Korsakov, before the Variophone itself was destroyed by a missile in the Nazi's siege of Leningrad.

KGB and The Soviet space program

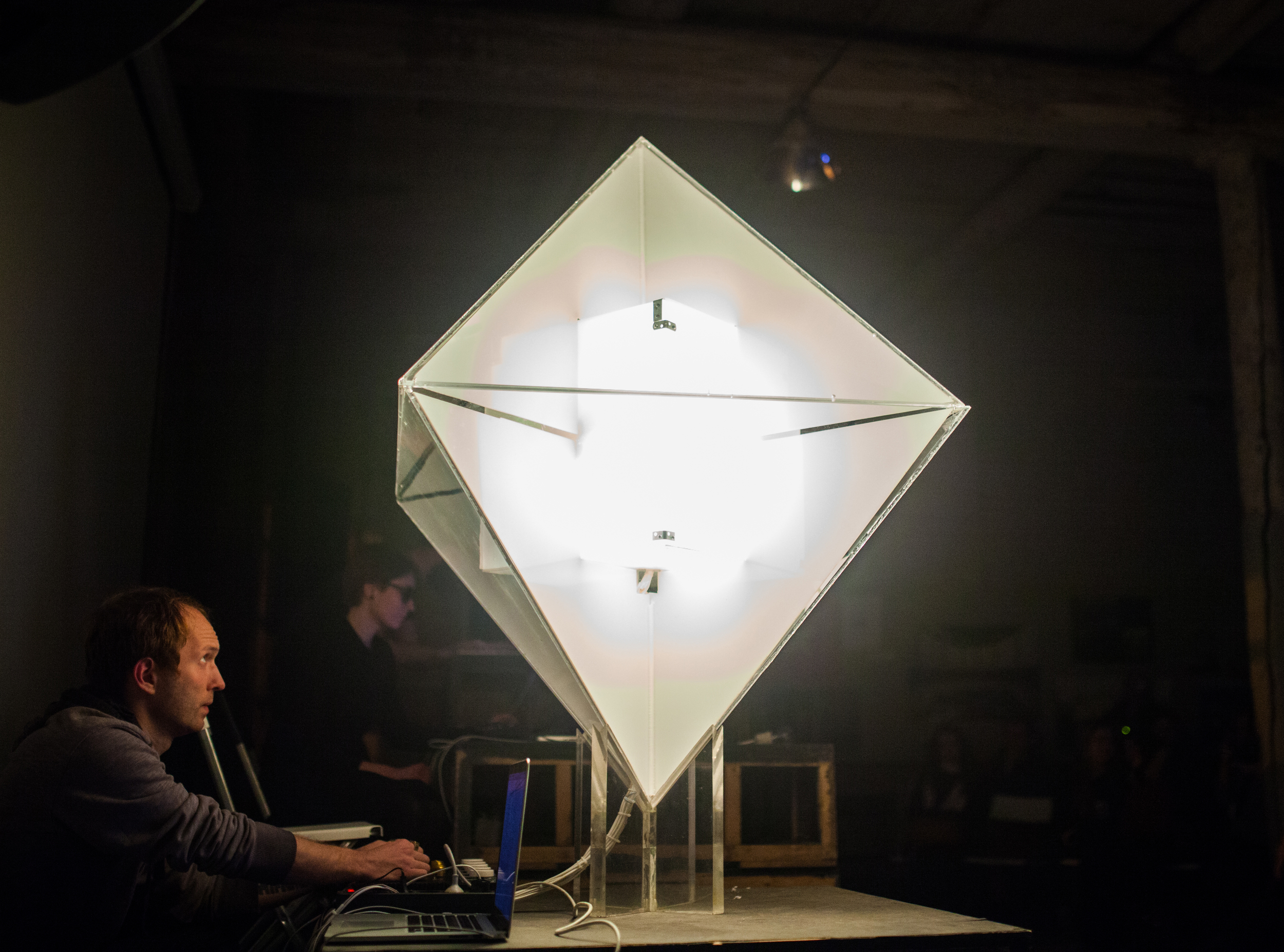

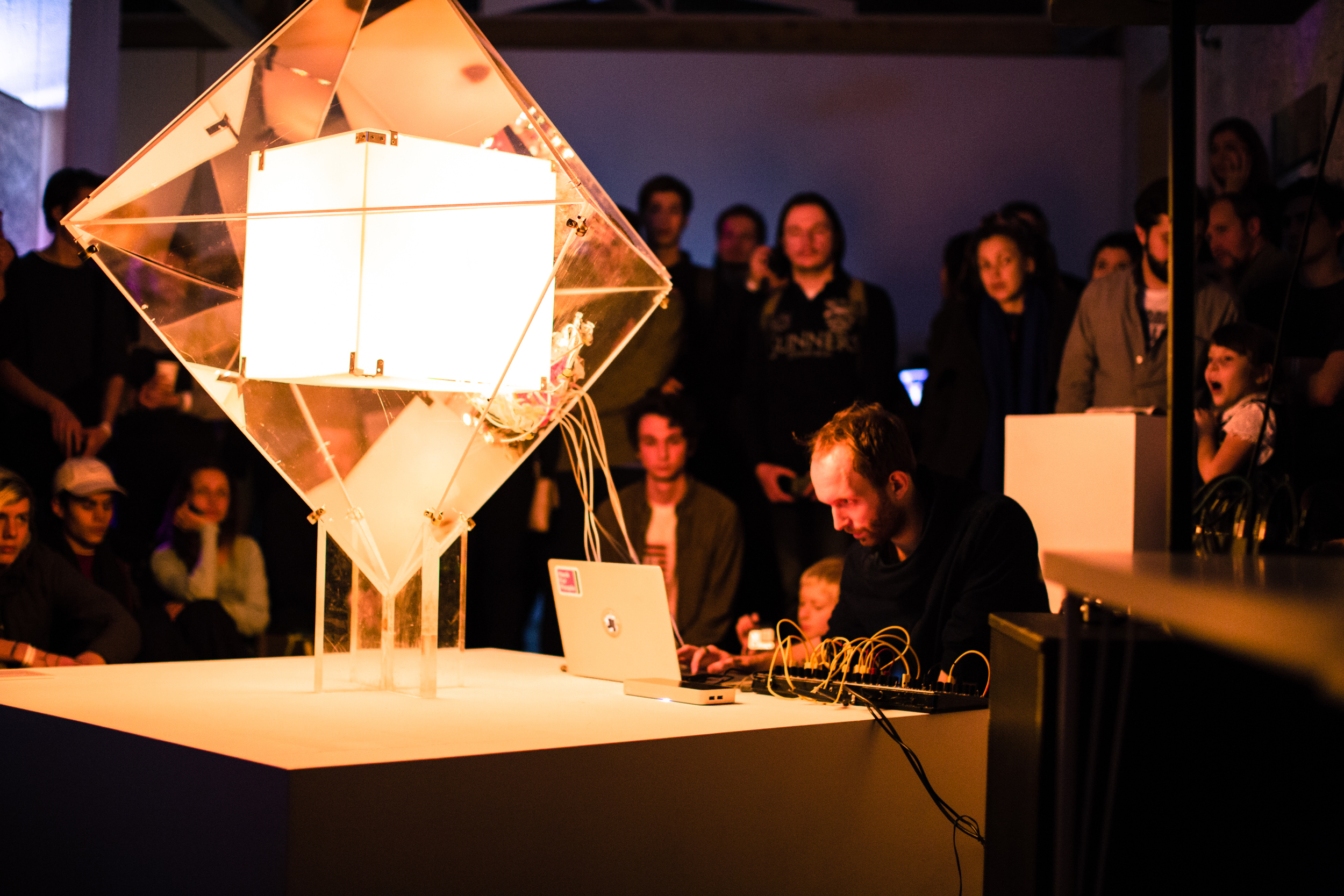

In fact, it's possible to imagine an alternative history of the synthesizer, one in which optical-electronic technology is employed in place of analogue (and later digital) circuitry. Drawn to the uniquely organic sounds that can be created, artists are reinterpreting this history, made accessible by the internet and by researchers like Andrey Smirnov, a specialist in the history of Russian visual and musical technologies. Derek Holzer and Mariska de Groot have each been inspired by the earlier inventions to work with the medium of opto-mechanical-electronic tone wheels. These spinning discs transform patterns of light and shadow into simultaneous sound.

Other works are just now coming to light. Some of these productions had military backing for research into the effects of audiovisual stimulation on different subjects. The KGB, Soviet air force and space program each supported the development of light instruments as technology that might eventually have intelligence or aerospace applications. Asking my Russian friends with some expertise in the area is itself a strange experience – they're initially surprised I don't know about the connection, then cagey about details, which were tightly classified in the age before Glastnost.

““The goal was to produce a kind of dance in light – a dance that could exist without being subject to the laws of gravity.””